The Age Barrier, And Its Costs

Why are teens, the elderly -- and, really, everyone -- ghettoized by age?

After my essay about learning from old men, I got some mail from readers who shared their own stories of wisdom shared by people old enough to be their grandparents. And it reminded me of something I’ve thought about before, the negatives of sorting people by age. If you look around our society, many of our more dysfunctional institutions are sorted by age: Homes for the elderly, public schools, even colleges. This age-segregation is artificial, something that never happened naturally in human society and barely happened at all until fairly recently in historical terms. Age segregation separates people from society, perhaps stigmatizes them, and, I think, harms society too.

It’s probably worst for teens. Putting kids together and sorting by age also created that dysfunctional modern creature, the “teenager.” Once, teen-agers weren’t so much a demographic as adults in training. They worked, did farm chores, watched children, and generally functioned in the real world. They got status and recognition for doing these things well, and they got shame and disapproval for doing them badly.

But once they were segregated by age in public schools, teens looked to their peers for status and recognition instead of to society at large. As Thomas Hine writes in American Heritage, “Young people became teenagers because we had nothing better for them to do. We began seeing them not as productive but as gullible consumers.” Not surprisingly, the kinds of behaviors that gain teenagers status from other teenagers differ from the kinds of things that gain teenagers status from adults: early sex, drinking, and a variety of other “cool” but dysfunctional characteristics—once frowned upon—now become the keys to popularity. When teenagers are herded together and separated by from adults, those behaviors gain in salience, and at considerable cost.

This is a phenomenon described in considerable detail by psychologists Joseph Allen and Claudia Worrell, in their Escaping the Endless Adolescence: How We Can Help Our Teenagers Grow Up Before They Grow Old. Although, they report, we’re often told that teenagers have “always been this way” and that they’re overly influenced by “hormones” or the “teenage brain,” the fact is that the modern teenager is a modern phenomenon, and teenagers in previous eras were far more responsible—and far more integrated into society as a whole. A hundred years ago, they note, teenagers “were not only essential to making a household run each day, but contributed almost a third of the family’s total household income.” Today’s teenagers, on the other hand, are largely consumers, not producers, something that now continues through college and even afterward. The resulting immaturity, they say, makes age 25 look like the new 15. Is that good? No, they report. This extended disconnection from the real world, at a time when people are, in many ways, at the height of their physical and mental powers, creates stress. “The average college student now reports as much anxiety as did the average psychiatric patient forty years ago.” And although schoolwork can be demanding, students know that it’s, in an important sense, not real.

Anderson and Worrell contrast school with the experience of a man named Pete who worked as a teenager in a men’s clothing store in New Hampshire in the 1970s, where he was the youngest employee by twenty years. The work wasn’t exciting, but people depended on him to get it right:

“Even at age fifteen I knew that folding shirts was kind of trivial,” he recalls. “Whether or not I flicked the cuffs in onto themselves just right to make them lie flat, I knew was not a life-changing event. What was a life-changing event was that I realized that these ‘men’s men’ weren’t going to consider me one of their club until I knew how to do it correctly, and I demonstrated that I could be relied upon to do it correctly again and again, because to them, even though they knew they were working in a relatively inconsequential job, this was the way that they displayed their pride, their craftsmanship. They let me know that it was important that I shared this focus, or I would never be trusted to be in the club. … This job also made me see that it was important that, every day, I show up, and on time because these guys were waiting to take their own break until I covered one of them in the store. So my being there was not some silly after-school job. It was, I began to see, a small cog in what made that place successful. … For me, that first job was a permanent character builder. It taught me: Show up on time. Do what you say you are going to do. Finish what you begin.”

Anderson and Worrell note, “These adult men had become Pete’s peer group.” After working there for a while, he reports, “I lost a bit of interest in gaining acceptance from my peers and realized that it was much more fun and more interesting to gain acceptance from people who you can learn a lot more from.” Pete was lucky because he got to experience something that too many kids don’t get to experience today—real work, outside school, with real adults.

My daughter got a similar experience. She left her suburban Knoxville high school after a single semester in 9th grade because she said it was wasting her time. She went to Kaplan’s Online College Prep School, did her schoolwork at night, and worked at a TV production company in Knoxville during the day. She was surrounded by high-functioning adults, and as part of her job got to sort the incoming resumés, a kind of experience few teenagers get. She graduated at 16 and went off to college, far more secure and confident in the adult world than most of her peers. (When she was 19 I asked her what she’d be like if she’d stayed in her fancy suburban high school: “Pregnant or on drugs or both, probably,” she said, based on many of her peers.)

Of course, as the authors above also note, not all work is equally character building. Although fast-food jobs can be a surprisingly rapid path to success for the motivated, most teenagers who start a fast-food job find themselves supervised by, basically, slightly older teenagers. This isn’t the same thing as working with mature adults.

In The Case Against Adolescence, psychologist Robert Epstein makes similar observations. Noting that teens, who used to be treated more like adults, are now so hedged about with restrictions that in California, they have to be 18 to have a paper route, he writes, “It’s likely that the turmoil we see among teens is an unintended result of the artificial extension of childhood.” Modern adolescence, he observes, is a modern invention, and most of the restrictions on teenagers that we take for granted are actually fairly recent in nature. Taking away the opportunity for teenagers to behave responsibly and earn respect from nonpeers just ensures the growth of a toxic “peer culture” that values appearance over achievement and rule breaking over responsibility.

Furthermore, nowadays that isolation from the adult world extends well beyond high school. Students in high school may now forgo work—if such work exists—so they can concentrate on grades, AP exam scores, and extracurricular activities (many basically bogus) aimed at getting them into a good college. Then, once in college, they may be encouraged not to work so as to focus on grades. In some sense, these may be wise moves, but in another, they mean that people can graduate college at 22—or, increasingly, 23, 24, or 25—without ever having really been in an adult-focused environment. Twenty-five really can be the new 15. Ironically, says Epstein, the evidence is that teens, given meaningful tasks, are just as capable of handling responsibility as most adults—who themselves can be irresponsible if treated like children. But “like children” is how our K-12 system (and, all too often these days, college) treats young people.

An education system that provided more opportunities for the kind of interaction that Pete enjoyed, above, would do more to build character and the kinds of skills that lead to real-life achievement. But, as Epstein notes, there are a lot of people who benefit from keeping teens infantilized. That includes people in our ever more expensive K-12 education system.

It’s not much better at the other end of life. I understand that some retirement communities reserve part of their space for people under 55, which seems like a good idea to me. Diversity! That’s the exception, though, not the rule.

But recently it occurred to me that teens are getting the shaft another way now. Not only are they segregated by age into schools, and kept out of the workplace to a substantial degree. Now they’re also segregated into social media apps. Not only are they physically isolated in the real world, but they’re electronically isolated on apps like Tik Tok, Yik Yak, Snapchat, and even to a degree Instagram. (Meanwhile, even though it originated on campuses, Facebook is now seen largely as an app for the middle-aged and older.)

Given that these apps are literally designed to be addictive, and to keep users “engaged” – that is, hooked online – as much as possible, there’s not much room for broadening there. And when you’re interacting online purely with people your age, you’re even more limited than when you’re interacting with them in real life. The “toxic peer culture” that Epstein describes becomes even more pronounced, and subject to even less moderation by adults, who are almost entirely excluded, than it does in school settings.

(I started writing this before the Nashville shooting took place, and I don’t know enough about the facts of that case yet to say whether the sort of isolation I’m describing played a role or not. It certainly has in some other cases, though, and a phenomenon can be bad even if it doesn’t fit in with the current news cycle. And I think age segregation is bad because it’s fundamentally at odds with human development as we have evolved to develop.)

Until the industrial age, kids, adults, and old people all lived in the same society. Kids learned from adults, quickly got responsibilities – some of them quite “adult” by today’s standards and many of them not at all safe – and gained their sense of accomplishment and self-worth from their standing in the larger community. Old people likewise were part of the same community, not struggling for status tokens in the walled-off society of Del Boca Vista Phase III.

A friend’s parents moved into an “independent living” facility that got turned into general housing and now many of the rather posh apartments in their building are occupied by a much younger post-college crowd. The parents were pretty salty about losing some of the amenities with the change (though they also got much cheaper rent) but they kind of like the more diverse and energetic atmosphere. Perhaps it will help keep them young. I’ve often thought that one reason why professors tend to live long has to do with being around people who are much younger.

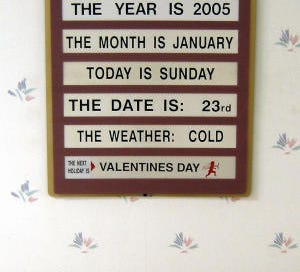

(A photo from the nursing home where my grandmother spent some time.)

It’s plausible, at least enough so to draw forth Chesterton’s Fence type concerns, that we evolved to function and flourish in an age-spanning setting, and that we might do worse at all ages when split up and segregated by age groups.

We’re certainly doing that experiment now. My advice for people of all ages is to spend some time outside your age cohort. It’ll benefit you, and it may benefit the people you’re with just as much.

Those are the benefits of overcoming age ghettoization. My question for you is, who does the current setup benefit, and how? And does that explain anything about the way things are?

Let me give you a heartening counter-example. I teach CS 428 (“real-world software engineering”) at Brigham Young University and have been doing so for six years. It’s an elective class, not required, but I get anywhere from 30 to 80 computer science seniors each semester, fall and winter. I teach it as a ‘survival’ course to prepare them to work in the real world. I have them read some classic works in the field, as well as some of my own posts and articles, and I tell them lots of stories from my industry experience verifying all the things they read.

Oh, and I turn 70 next month. That “industry experience” spans almost 50 years.

The CS department has already asked me to teach this coming fall and winter as well. I’m happy to keep doing it as long as I can, because I’m passionate about the subject, and because I keep getting emails from former students that say, “It’s true. Everything you said is true.” 🤣

This is the best of your Substack posts that I have read. It could very easily be turned into a head-turning book. But does anyone read books these days? Am I the last?