Is wokeness a religion? And why is libertarianism unlikely to catch on broadly?

I’ve been thinking about these things for a while, and I’m pretty sure there’s a connection.

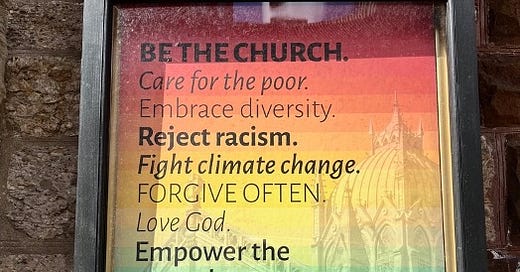

As this photo from Boston’s Old South Church indicates, wokeness is viewed as such by many of its adherents, and by many affiliated with organized religions.

You can find similar rainbow-hued declarations at houses of worship — most of them less venerable — all over the country. And you can find more or less identical declarations sprouting from the lawns of homes in leafy blue suburbs around the nation, too.

Whether or not these sentiments would have found favor with the 17th Century Puritans of Boston (a few would, most not so much, I suspect — “Love God” would no doubt have become “fear god,” “reject racism” and “fight climate change” would probably have been more or less incomprehensible, and “care for the poor’ would have been tempered by a degree of tough love that would be equally incomprehensible to moderns. (And I dare you to ask Cotton Mather about the importance of an “enjoy this life” philosophy; never mind his father Increase.)

But the sentiments themselves are everywhere. And they’re mixed up with religion. Just this week, the University of Helsinki gave Greta Thunberg a Doctorate in Theology. That kind of says it all.

Well, these things don’t just happen. When waves of sentiment sweep the country, and the world, it may be partly because people and organizations are pushing them. But they also have to meet some sort of unmet need among a significant segment of the populace. And laugh at wokeness all you want — no, I mean, seriously, laugh at wokeness all you want — but the people who wallow in it, every bit as much as the people who push it, are getting something out of it that they’re not getting elsewhere. It’s not happening in a vacuum, and it’s not entirely a top-down push by any means.

Exactly what they’re getting varies, but I think a lot of it is feeling like they’re part of something. It’s a source of bonding, a source of self-worth, and — importantly — an excuse to treat members of the out-group badly. Many people are happy to have an excuse to treat other people badly and to feel good about it, and all sorts of ideologies, including but not limited to religion, provide that in various forms.

It’s tempting to dismiss this sort of thing as a human flaw, and in many contexts it is. But it’s also an aspect of being human, and perhaps even the most important aspect because for much of human history it wasn’t a flaw, but an asset. We’re here in no small part because our ancestors were good at sticking together in groups, and in beating out, or exterminating, their enemies.

Humans in the Stone Age era were weak. Individually, even armed with spears, they were easy prey for all sorts of animals. In groups, they drove mammoths and saber tooth tigers into extinction. The humans who survived had these characteristics: Religion, and Revenge.

Revenge because, when a lion kills a zebra, the remaining zebras don’t start stomping lions to death when they encounter them. When a predator kills humans, historically humans have killed them back. (Except for the modern types who love monsters. But they may be the exceptions that prove the rule.) Likewise other humans who killed members of the tribe, which happened a lot in what was, despite wishful thinking on the part of some archaeologists, a very violent era.

Religion, in all sorts of forms, helped bond the tribe together, and also to differentiate them from the Others, the enemy. (Most primitive peoples today have names for themselves that translate into something like The Real People, not like those subhumans over the hill. This was likely the case back then, too),

My hypothesis is that modern humans have an instinct for religion, probably even a gene or gene-complex for one. We’re the descendants of the tribes that stayed together.

Religion wasn’t the only binding agent. Another was leaders. Based on observation, I’d say that about 80% of people basically want to be led. They might, in extremis, rise up against a bad enough leader, but probably just in the hope of a better one. About 15% want to be leaders of some sort – not necessarily top dog, but able to exercise authority over their peers. The remaining 5%, more or less, don’t want to be either followers or leaders in general. They might be either from time to time, situationally, but are not drawn to be one or the other. (You can argue about the numbers here, but I think they’re pretty close, and the relative proportions are too).

That’s probably genetic, too. Leaders have a lot of downsides. They’re self-centered, they’re often incompetent, they’re disproportionately likely to be sociopaths, their usually disproportionate reproductive success comes at the expense of those of lesser rank. But leadership was essential to the survival of early human bands, and it was essential enough to survive despite the other tradeoffs. Primitive tribes made up exclusively of libertarians who didn’t get together quickly in the face of danger probably didn’t survive very well.

Of course, the thing about the religion gene (you can call it an “inherited tendency” if you prefer, which is fair enough – it may be the product of more than a single gene) is that it’s not super-picky about which religion. Aztec human sacrifice or the Heaven’s Gate cult appeal to it just as much as Christianity, Judaism, or Hinduism. It doesn’t care what God thinks, only about a belief strong enough to inspire cohesion and self-sacrifice on behalf of the group. (In some strands of religious belief, you might even think that this tendency is something that demons can take advantage of).

Because the religion gene isn’t picky, Keith Henson’s views about the value of tried-and-safe religious belief (“memes” in this context are mind-viruses, self-reproducing ideas, not pictures of cats with funny text) make sense:

I have picked dangerous examples for vivid illustrations and to point out that memes have a life of their own. The ones that kill their hosts make this hard to ignore. However, most memes, like most microorganisms, are either helpful or at least harmless. Some may even provide a certain amount of defense from the very harmful ones. It is the natural progression of parasites to become symbiotes, and the first symbiotic behavior that emerges in a proto-symbiote is for it to start protecting its host from other parasites. I have come to appreciate the common religions in this light. Even if they were harmful when they started, the ones that survive over generations evolve and do not cause too much damage to their hosts. Calvin (who had dozens of people executed over theological disputes) would hardly recognize Presbyterians three hundred years later. Contrariwise, the Shaker meme is now confined to books, and the Shakers are gone. It is clearly safer to believe in a well-aged religion than to be susceptible to a potentially fatal cult.

So if you want to look at it through a biological metaphor, wokeness is like a virus that employs the same receptors that traditional religions do. And it’s probably easier for it to take over the minds of those whose religion receptors aren’t already occupied by something solid. (Cue the G.K. Chesterton quote about how those who don’t believe in God don’t believe in nothing, but instead will believe in anything.)

And, continuing the wokeness virus metaphor, it might even evolve to look more like traditional religions, and maybe even to displace them. (See the Old South Church sign above.) Much as the HIV virus mimics T cell receptors to fool the immune system and gain entry to cells, so wokeness mimics traditional religions so that it can escape people’s skepticism and enter their minds more easily via the mental religion receptors.

Okay, these biological metaphors can go too far, but I think this one holds up pretty well.

What I think it means, at any rate, is that most people’s minds are tuned to believe, and if they don’t believe in traditional religion, they’re probably more likely to find a substitute religion in some other similar mental construct. (And of course, just as a monoculture of plants is easily overrun by a single virus or parasite, so too an intellectual monoculture is more easily run over by a viral idea).

Now add to that that 80% of the population, more or less, is inclined to be told what to do, and a monoculture made up of largely nonreligious leaders is particularly vulnerable to the “woke mind virus,” to use Elon Musk’s phrase. And in fact, we see today that wokeness is particularly popular among the ruling class and its hangers on.

Genetics is probably also why we libertarians aren’t likely to be as influential as we’d like to be. We joke about taking over the world and ruthlessly leaving people alone, but that’s hard when most people don’t really want to be left alone, they want to feel that they’re taken care of. The imagery may be of a stern, demanding father, or a bountiful (but controlling) mother, but to many people, that’s more appealing than being truly independent. And if they don’t get it from religion, they’ll get it from government or something else.

Once upon a time, I had great faith in the ability of libertarians to persuade people of the benefits of freedom. But I’m increasingly reminded of Sallust: “Few men desire liberty; most men wish only for a just master.” You can’t easily reason people out of something they were never reasoned into, and the tendency to want someone to be in charge isn’t the product of reasoning.

Well, that’s perhaps too gloomy, but it captures the point. So what’s the takeaway?

I’m not sure. (And one of the things I like about the Substack format is that I can think out loud in a way you can’t easily do in an oped or a magazine article, where editors – and readers – like you to tie things up into a neat package at the end.) But:

It’s not pointless to criticize leaders, or popular mind-viruses. Some people are completely immune to persuasion, but others are not, and the people most immune to persuasion are probably the most willing to shift their stance when they see the momentum going the other way. Of such are preference cascades made. And there’s both a practical and a spiritual value to pointing out the truth, even when it doesn’t immediately change many minds.

And the leaders themselves are vain enough that they can be moved even by criticism that is unlikely to have any tangible effect. They desire to feel important, and surprisingly often, to feel loved. (Nicolas Ceaucescu genuinely believed his people loved him almost until the very end. Preference falsification doesn’t just fool followers, but leaders too, though the consequences of its breakdown tend to be more painful for the latter, as Ceausescu found out first-hand.) They are thus surprisingly sensitive to criticism. Sometimes that leads them to lash out, but the more they are constrained against that, the more likely they are to listen to criticism, or at least try to avoid it by changing their actions.

Which is maybe the takeaway here. If we can’t stop people from wanting to believe in something, and if it’s inevitable that most people will want to have, or be, leaders, then it’s important that we have structures that allow the ideas, and the leaders, to be criticized. That’s one of the most important functions of things like free speech, free association, and the like. It was also the inspiration for the religious establishment clause, but now that our “religious establishments” involve more than traditional religion, maybe that bit needs more work.

Maybe we can draw guidance from Adlai Stevenson: My definition of a free society is a society where it is safe to be unpopular. Most totalitarian societies – oh, who am I kidding, all totalitarian societies – aim for just the opposite.

Make it safe to be unpopular, and you will make society freer. I’m for that.

I'm so glad you're using Substack to let your mind off the leash of cookie-cutter space constraints. Shorter, longer -- it should fit the size of the thoughts and ideas you want to explore. This is great!

You present a great argument, but why does it infect only a small segment of the population? Refer back to the McMartin prosecutions, where it infected only selected segments of police, social workers, and the judiciary. It lasted for years and then died out. Both then and now normal folks were not convinced. There must be an element of peer pressure within the selected group to make this work. And that element does not extend to the broader population. If the people are not buying what the elites are selling, what are the prospects for the elites continuing? From 40 years ago, a cartoon captioned "There they go and I must hurry, for I am their leader."