Thoughts on our ruling class monoculture

And on what to do about it. Plus a request for further ideas.

Our modern ruling class is peculiar. One of its many peculiarities is its penchant for fads, and what can only be called mass hysteria. Repeatedly, we see waves in which something that nobody much cared about suddenly comes to dominate ruling class discourse. Almost in synchrony, a wide range of institutions begin to talk about it, and to be preoccupied by it, even as every leading figure virtue-signals regarding this subject which, only a month or two previously, hardly any of them even knew about, much less cared about.

There are several factors behind this, but one of the most important, I think, is that our ruling class is a monoculture.

In agriculture, a monoculture exists when just a single variety dominates a crop. “Monoculture has its benefits. The entire system is standard, so there are rarely new production and maintenance processes, and everything is compatible and familiar to users. On the other hand, as banana farmers learned, in a monoculture, all instances are prone to the same set of attacks. If someone or something figures out how to affect just one, the entire system is put at risk.”

In a monoculture, if one plant is vulnerable to a disease or an insect, they all are. Thus diseases or pests can rip through it like nobody’s business. (As John Scalzi observes in one of his books, it’s also why clone armies, popular in science fiction, are a bad idea in reality, as they would be highly vulnerable to engineered diseases.) A uniform population is a high-value target.

This is also why nature fosters genetic diversity. Sexual reproduction is a lot of trouble compared to, say, fission or budding, or even parthenogenesis. Despite its undoubted pleasures, it’s resource-expensive, requiring a search for a mate, possibly competition to mate at all, and risks like sexually transmitted diseases and childbirth, all for a paltry 50% (average) genetic pass-on. Unlike asexual reproduction, which produces a copy of what is, by definition, a successfully reproducing individual, sexual reproduction produces a genetically unique offspring who may turn out to be worse-adapted to the environment than either parent.

But on the other hand, it produces a genetically unique offspring. This means that parasites that might be well adapted to the parents may well be less adapted to the offspring. Sexual reproduction imbues a population with genetic diversity, making it a moving target for diseases, parasites, etc.

This isn’t the first time I’ve thought of this phenomenon in a political connection. I’ve written elsewhere, in a law review article titled Is Democracy Like Sex? that electoral turnover in democracies produces a moving target for special-interest groups (the political analog of parasites) and thus helps keep them from becoming too well adapted to the society that is their host. As evolutionary biologist Thomas Ray observed, every successful system accumulates parasites, and the United States of America has been very successful indeed. I suggested that part of its success lay in electoral shifts that served keep special interests from locking in their positions entirely.

But what I (mostly) missed when writing that piece many years ago, is that electoral turnover only affects one small piece of society. While elections change out elected officials sometimes, the rest of our society – the bureaucracy, academia, media, corporate leadership, what is generally known as the “gentry” or “ruling class” – remains the same.

And our ruling class today is very much a monoculture. As Angelo Codevilla wrote in a seminal essay on America’s ruling class:

Never has there been so little diversity within America’s upper crust. Always, in America as elsewhere, some people have been wealthier and more powerful than others. But until our own time America’s upper crust was a mixture of people who had gained prominence in a variety of ways, who drew their money and status from different sources and were not predictably of one mind on any given matter. The Boston Brahmins, the New York financiers, the land barons of California, Texas, and Florida, the industrialists of Pittsburgh, the Southern aristocracy, and the hardscrabble politicians who made it big in Chicago or Memphis had little contact with one another. Few had much contact with government, and “bureaucrat” was a dirty word for all. So was “social engineering.” Nor had the schools and universities that formed yesterday’s upper crust imposed a single orthodoxy about the origins of man, about American history, and about how America should be governed. All that has changed.

Today’s ruling class, from Boston to San Diego, was formed by an educational system that exposed them to the same ideas and gave them remarkably uniform guidance, as well as tastes and habits. These amount to a social canon of judgments about good and evil, complete with secular sacred history, sins (against minorities and the environment), and saints. Using the right words and avoiding the wrong ones when referring to such matters — speaking the “in” language — serves as a badge of identity. Regardless of what business or profession they are in, their road up included government channels and government money because, as government has grown, its boundary with the rest of American life has become indistinct. Many began their careers in government and leveraged their way into the private sector. Some, e.g., Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner, never held a non-government job. Hence whether formally in government, out of it, or halfway, America’s ruling class speaks the language and has the tastes, habits, and tools of bureaucrats. It rules uneasily over the majority of Americans not oriented to government.

Codevilla wrote the essay over a decade ago, and it has only grown more true in the interim. Despite its constant invocation of “diversity,” in many important ways our ruling class is much less diverse than it has ever been. And, as a monoculture, it is vulnerable to viruses of a sort. Including what amount to viruses of the mind.

When Elon Musk referred to the dangers of the “woke mind virus,” he knew exactly what he was talking about. Ideas can be contagious, and can be viewed as analogous to viruses, entities that reproduce by infecting individuals and coopting those individuals into spreading them to others. Richard Dawkins, in his The Selfish Gene, coined the term “meme” to describe these infectious ideas, though the term has since acquired a more popular meaning involving photos of cats, etc. with captions. And yet those pictures are themselves memes, to the extent they “go viral” and persuade others to copy and spread them.

Our ruling class is particularly vulnerable to mind viruses for several reasons. First, it is a monoculture, so that what is persuasive to one member is likely to be persuasive to many.

Second, it suffers from deep and widespread status anxiety – not least because most of its members have status, but few real accomplishments to rely on – and thus requires constant reassurance in the form of peer acceptance, reassurance that is generally achieved by repeating whatever the popular people are saying already. And third, it has few real deeply held values, which might otherwise provide guard rails of a sort against believing crazy things.

In a more diverse ruling class, ideas would not spread so swiftly or be received so uncritically. People with different worldviews would respond differently to ideas as they entered the world of discourse. There would be criticism and there would be debate. (Indeed, this is how things generally worked during the earlier, more diverse, era described by Codevilla, though intellectual fads – lobotomy, say, or eugenics – spread then, too, though mostly through the Gentry/Academic stratum of society that now dominates the ruling class.)

Also, a society in which people hold firm beliefs on important moral and ethical issues is less vulnerable to rapid swings in many areas. “Guard rails,” as I said. Keith Henson said it well in a famous (pre-Internet, or at least pre-Web) essay on memes. Looking at the damage done by all sorts of fatal memetic outbreaks, including Nazism, Jonestown, and Pol Pot’s Cambodia, he observed:

I have picked dangerous examples for vivid illustrations and to point out that memes have a life of their own. The ones that kill their hosts make this hard to ignore. However, most memes, like most microorganisms, are either helpful or at least harmless. Some may even provide a certain amount of defense from the very harmful ones. It is the natural progression of parasites to become symbiotes, and the first symbiotic behavior that emerges in a proto-symbiote is for it to start protecting its host from other parasites. I have come to appreciate the common religions in this light. Even if they were harmful when they started, the ones that survive over generations evolve and do not cause too much damage to their hosts. Calvin (who had dozens of people executed over theological disputes) would hardly recognize Presbyterians three hundred years later. Contrariwise, the Shaker meme is now confined to books, and the Shakers are gone. It is clearly safer to believe in a well-aged religion than to be susceptible to a potentially fatal cult.

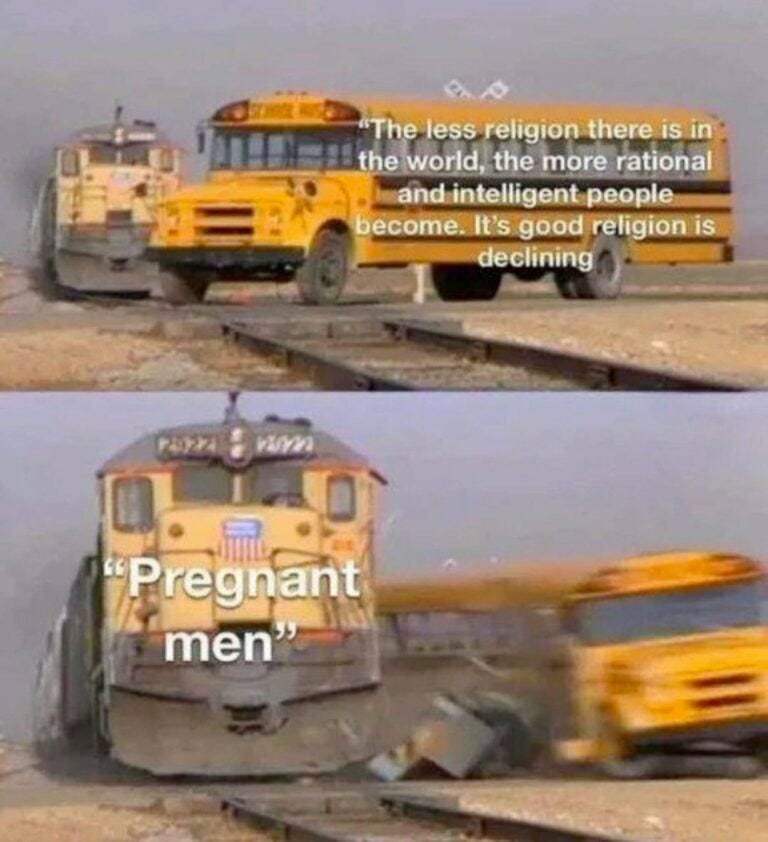

Note that even an atheist might prefer a society in which most people believe in safely-aged religions to one in which dangerous idea-viruses are more likely to run rampant. As G.K. Chesterton famously said, “When men choose not to believe in God, they do not thereafter believe in nothing, they then become capable of believing in anything.”

A similar sentiment was captured in this, yes, meme I’ve seen circulating on social media:

It may even be the case that people who wanted to spread certain sorts of ideas in society found it advantageous to reduce the influence of “well-aged religion” because they saw it as a barrier. Likewise, the promotion of a cult of youth-as-wisdom helped to insulate younger people from the experience of their elders, diminishing the influence of a potential moderating force.

Well, perhaps that is a digression, though perhaps not. But what should we do if we want a less-hysterical, more sensible ruling class? (My own preference would be not to have a ruling class at all, but that’s basically impossible, I think, given aspects of the human character that are better discussed in another essay. And as the saying goes, even in an anarchy, if it is functional you will find a well-established old boys’ network.)

First, it would be good to diversify our ruling class. Since a major reason for its uniformity is that its leaders are educated in the same schools – often literally the same handful of schools, but if not then in “lesser” schools that do their best to emulate the top ones – we should first pursue more diversity in schools, and second try to minimize the relevance of education in terms of membership in the ruling class.

It’s possible that the voting populace’s growing hostility to the credentialed class will promote that to a degree. We should also try to foster the development of tycoons. Sometimes (*cough* Mark Zuckerberg *cough*) they just ape the rest of the ruling class. But other times, as with Elon Musk, they are disruptive forces. (One might even say that J.K. Rowling, a tycoon of sorts herself, is playing a similar disruptive role in the trans debate). More openings for disruption are good.

Second, religion isn’t the only guardrail. In America, the Constitution plays an important role, and while I’m somewhat disappointed overall in the performance of the judiciary, it has nonetheless been a barrier to the worst of wokeness. The Constitution also creates markers for what represents a departure from American tradition and values, which is useful. A judiciary more willing to be aggressive would help.

Third, people should have to do their jobs. CEOs, professors, and politicians who pursue fashionable social goals are usually doing this in preference to their actual jobs. CEOs’ jobs involve making money for shareholders, and stricter readings of fiduciary duties should hold them to that job. Keeping their mind occupied with profits and losses will leave less space for fashionably kooky ideas. Likewise professors and politicians. You shouldn’t get to substitute social posturing for teaching The Rule Against Perpetuities or fixing potholes. People who have to stick to their knitting are probably less distractable, and less capable of doing harm if they are distracted.

Also, just an awareness of what’s going on may help. When Elon Musk talked about the “woke mind virus,” he wasn’t just reacting to a dangerous meme, he was spreading the protective notion that infectious bad ideas circulate among our ruling class. Mass hysteria and social posturing should be called out as such.

But calling out these things can get you mobbed. Being a tenured professor is (some) protection, and so is having independent sources of income, but most people don’t have tenure or independent means. (Making it easier to have independent incomes, and reducing the power of HR and other bureaucrats over people’s jobs, would help.) I also favor making it easier to sue people for mobbing. It’s yet another subject for another essay, but along with stronger libel laws, which are to be desired, many existing business torts and civil rights actions are potentially deployable against social media mobbers. J.K. Rowling is illustrating how effective that can be right now.

Rowling is fabulously rich, of course, which makes her threats more credible. But I’ve successfully threatened libel action to make people withdraw false and malicious statements on Twitter. And if it gets started, there will soon be lawyers who will take these cases on a contingent-fee basis. There might even be a market for some sort of insurance against being mobbed, in which a modest premium means the mobbers will be hassled by lawyers. Win or lose, “the process is the punishment” as they say.

In short, I’m in favor of various societal guardrails that will limit the effective range of crazy actions to a degree, along with consequences and focus that will reduce their appeal. These are just a few thoughts, and this rambling essay has gotten long enough already. But there’s more to talk about. Please add your thoughts in the comments.

A big part of the problem is that the multiple ladders of success which have existed in American society are increasingly being collapsed into a single ladder, with access tightly controlled via educational credentials. More than 50 years ago, Peter Drucker asserted that a major advantage of America over Europe was the nonexistence of 'elite' educational institutions with overweening power over admissions to key positions in society:

"One thing it (modern society) cannot afford in education is the “elite institution” which has a monopoly on social standing, on prestige, and on the command positions in society and economy. Oxford and Cambridge are important reasons for the English brain drain. A main reason for the technology gap is the Grande Ecole such as the Ecole Polytechnique or the Ecole Normale. These elite institutions may do a magnificent job of education, but only their graduates normally get into the command positions. Only their faculties “matter.” This restricts and impoverishes the whole society…The Harvard Law School might like to be a Grande Ecole and to claim for its graduates a preferential position. But American society has never been willing to accept this claim…"

American society today is a lot closer to accepting that claim than it was when Drucker wrote.

More excepts from Drucker on education here:

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/26133.html

Another fine musing Perfesser. I agree that our libel and slander laws could use a deep updating; the only other option being, perhaps, the return of dueling which, may have to come first.

It is astonishing to consider the speed with which the Woke psychosis (not too strong a word I think) infected the American credentialed class though that in turn points to its origin, viz., the Academy. And if the Academy is the origin, how did that happen? Yes, the march of the Left through the humanities and the "social sciences" was known and observed with the requisite "tsk tsk" by the extant professoriate at the time it happened, and it was tolerated there, but now we have arrived at a place where Math and Science are denounced as racist and oppressive. Where free speech is racist and oppressive. Where any deviation from the Woke dogma is attacked, often with violence.

I think the blame can be placed on cowardice. Yes, plain ordinary, simple human cowardice. The leadership in the Academy are cowards as are most of the administration and professoriate.

Which begs the question, how then did cowards come to lead and administer the Academy?