The Elvis Problem

Defining religion under the First Amendment

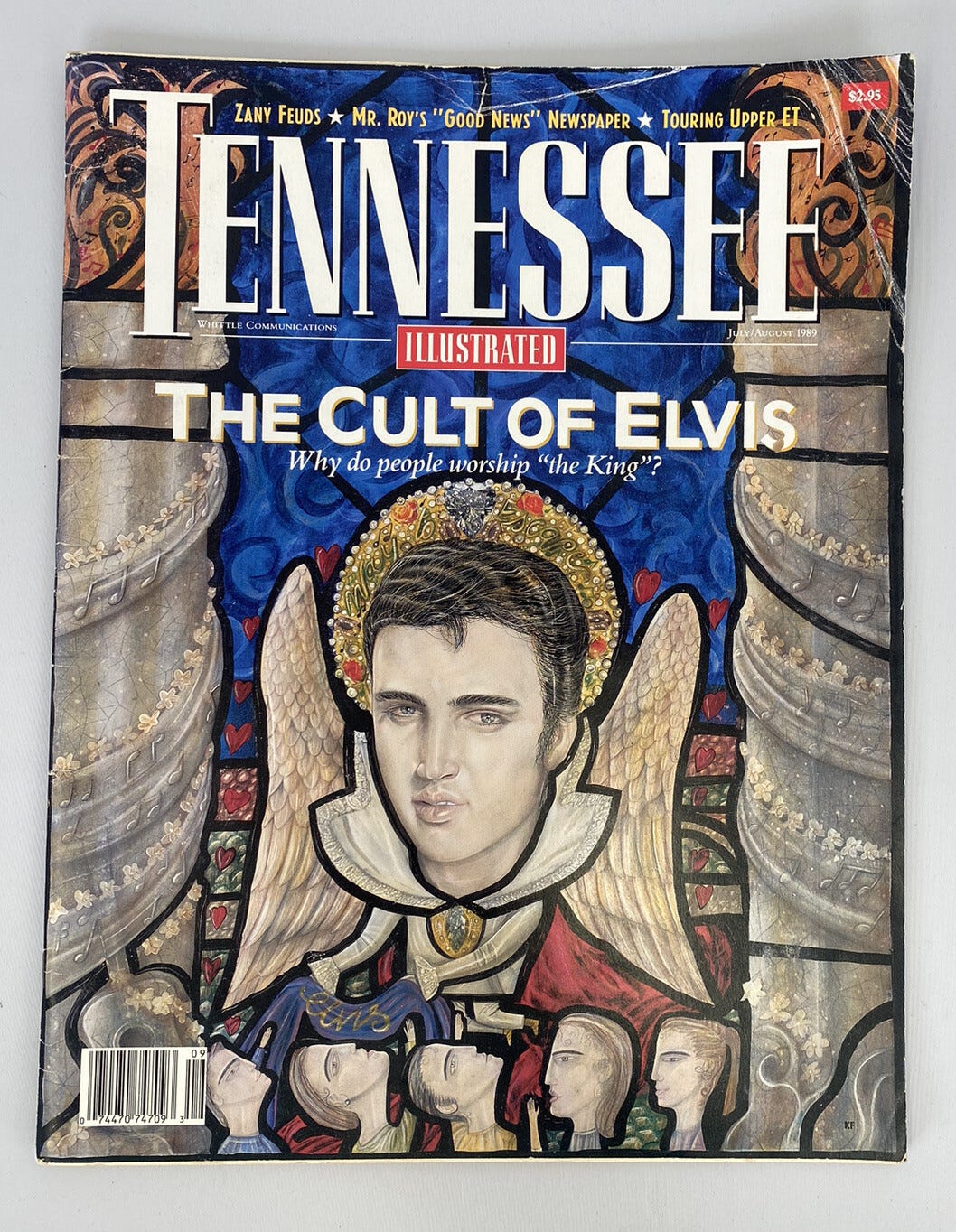

Imagine a charismatic figure, worshiped by millions. From humble beginnings, he gains followers across America, and around the world. Huge crowds flock to see him.

After his death, his cult lives on. Dressed like him and imitating his voice and mannerisms, an entire priesthood grows up, even performing marriages and other sacraments. Despite his reported death, people report seeing him in various locations, and even credit him with miracle cures. His relics are treated as holy objects. (Saints’ fingerbones circulated in medieval Europe. For him it’s toenails and a wart removed by a dermatologist.) The faithful make pilgrimages to his former home, suggestively named Graceland.

Yes, I’m talking about Elvis. The cult of Elvis Presley lives on.

See. People worship him. But is it a religion?

Well, that depends, doesn’t it, on what a religion is.

This is one of the questions that Josh Blackman identifies as vital if the Supreme Court’s opinion in Employment Division v. Smith is overturned. Smith held that a neutral law of general application is valid under the free exercise clause of the First Amendment even if it burdens someone’s religious practice.

Blackman writes:

In Smith, Justice Scalia worried that the Sherbert test allowed every person to become a law unto himself. In other words, a person could gain an exemption from the law by dressing up his political, philosophical, or moral views in the garb of religion. Smith had a religious claim to using a controlled substance, but other people who like to use the same substance may not have the same religious bona fides. For the Free Exercise Clause to be triggered, there has to be religion. What, then, is religion? In most cases, this issue is fairly straightforward. Well-established faiths that have been around for a long time--especially those in existence when the First Amendment was framed--would be religions.

The harder cases would involve new, or recent, faiths. This inquiry blends into the sincerity inquiry. Is this religion an actual religion, established for religious reasons? Or was this religion manufactured for the purpose of gaining exemptions from the law? For example, what if a drug dealer establishes the Church of the Holy Marijuana Leaf, and ordained all of his dealers as ministers?

There is an even harder question lurking under the surface: what about a group that calls itself religious, but rejects all of the traditional indicias of religion. For example, the organization rejects the idea of any higher power, has no rituals, imposes no actual obligations, and so on. Perhaps the organization professes some sort of moral code, but that code has no grounding in anything that traditionally would be understood as religious. If you can tell, I keep using the word tradition. Is there a "history and tradition" approach to deciding what is a religion? Would we consider how the Framers of the First Amendment would have understood a religion? I don't have an answer to these questions here, I am simply raising them.

I have some potential answers, but we’ll get to that later.

Courts can dodge this sort of thing with the “sincerity” inquiry. Courts can’t look into the truthfulness of religious beliefs — that would violate the establishment clause of the First Amendment — but they can look into the question of whether people asserting free exercise rights actually believe in the things that they are claiming should grant them an exemption from the law.

Thus one of my favorite free exercise cases, involving one Mary Ellen Tracy and her pagan temple, which featured a practice called, somewhat pejoratively, (and out of favor among modern religious historians, who prefer the term “sacred sex”) “temple prostitution.” Under pagan doctrine, an orgasm brought men, for a second or two, onto the plane of the gods. This was especially true if the orgasm was brought on by a consecrated priestess of the god or goddess in question. You showed up, made an offering, and had sex with a priestess or consecrated female worshipper (depending on the temple). Was this prostitution? Is a church that gives you a wafer and a sip of wine after you put something in the collection plate a restaurant?

Modern “gender scholars” have expressed doubts about the validity of this tradition, which to my mind is probably a reason to take it more seriously. But anyway, Tracy ran a “temple” that authorities busted as a house of prostitution. Here’s Grok’s summary, which is pretty good (links to more background at the link):

The story. . . dates back to the late 1980s and involves Mary Ellen Tracy (also known as Sabrina Aset), a high priestess who co-founded the Church of the Most High Goddess with her husband, Wilbur Tracy, in Los Angeles. The church, inspired by what they claimed were ancient Egyptian religious traditions, operated out of their West Los Angeles home and promoted "sacred prostitution" as a form of spiritual ritual. Tracy asserted that she acted as a priestess, engaging in sexual acts with male congregants (and sometimes women) to cleanse their spirits and connect them with the divine. She later claimed to have performed these rituals with over 2,000 men as part of the church's practices.

The couple argued that these activities were protected under the First Amendment's free exercise of religion clause, framing the church as a legitimate neo-pagan organization reviving temple prostitution from antiquity. However, authorities viewed it as a front for illegal prostitution, especially since participants were required to make "donations" to the church in exchange for the rituals.

In April 1989, police raided their home on West 5th Street, arresting both Tracys on charges of pimping, pandering, and prostitution. During the trial, Mary Ellen Tracy testified that the sexual acts were religious in nature, but prosecutors countered that the setup was essentially a brothel. In September 1989, a jury convicted them: Wilbur received 180 days in jail and a $1,000 fine, while Mary Ellen was sentenced to 90 days in jail, three years' probation, and mandatory STD testing.

The couple appealed, reiterating their First Amendment defense, but in May 1990, a federal judge ruled that the church was merely a cover for prostitution and rejected their constitutional claims. Their convictions were upheld, and the religious protection argument failed.

The case drew media attention at the time, with appearances by Tracy on talk shows like Donahue and The Montel Williams Show, and it has been referenced in discussions of sacred prostitution and religious freedom ever since.

One of the great advantages of Smith, of course, is that you don’t have to look into these things. A general law against taking money for sex burdens your particular — sincere and legitimate — religious practice? Tough. Ask the legislature for an exemption, the Constitution doesn’t help, just as it didn’t help the two fired drug counselors in Smith, whose use of peyote in Native American Church services was undoubtedly sincerely religious in nature. (Given the fairly ugly side effects of peyote, few people would use it recreationally, at least more than once).

Overrule Smith and you’re down in the weeds. This, I suspect, is why the overruling of Smith is less likely than many scholars, looking simply at doctrine, may believe. When it comes down to brass tacks, judges, or justices, are little more eager to make their lives and jobs harder than anyone else.

Blackman asks if we would consider how the Framers viewed freedom of religion. That’s tricky. Some Framers seem to have thought of religious freedom as applying mostly among different Christian denominations, though there were occasional more-general statements, such as that contained in George Washington’s letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Rhode Island, which was pretty universal: “The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

There were also occasional statements from Jefferson, Franklin, etc. to the effect that religious toleration extended even to “Mahometans,” and the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli provided that “As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion,-as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen,-and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.”

That said, the chief background for the First Amendment’s religion clauses was experience. And that experience was of religious war — between Catholics and Protestants, between Protestants of the Puritan variety and the Church of England, etc. — and one of the chief purposes of both the free exercise and the establishment clause was probably to tamp that sort of thing down. By providing that government couldn’t be used to advance or repress particular religions, it gave everyone less cause to resort to arms to take control of it, or to prevent their enemies from taking control of it.

How that might affect a definition of religion if Smith is repealed is left as an exercise for the reader, as the old mathematics textbooks used to say. But if that’s what the clauses are really about, then is the true definition of religion that set of beliefs that people are willing to kill or die for? And where does that take us?

[As always, if you like these essays, please take out a — preferably paid! — subscription. I will thank you, and my family will thank you.]

Most people today, including a lot of judges, do not understand what the term "establishment of religion" meant in the 1700s. Most European countries had "established" churches--official churches, favored by the government; in many countries, other churches were banned. Even most of the American colonies had established churches--the Church of England in New York and the southern colonies, the Congregational (previously known as the Puritans) in New England.

In England, Wales, and Ireland, the Church of England had both power and special privileges. Bishops and archbishops of the Church of England had seats in the House of Lords, the upper house of Parliament. In order to hold any public office, you had to take Communion in the Church of England; for a long time, you had to be in the state church even to vote. In Ireland in the 1700s, if you wanted to be legally married, you had to have the ceremony in an Anglican church; this and other oppressions were a factor in the mass emigration of Presbyterian Ulster Scots to the American colonies between 1715 and 1775 (later called Scotch-Irish to distinguish them from the Catholic Irish who came to America during the potato famine of the mid-1800s).

When the Bill of Rights was added to the Constitution, the decision was made not to have an official, "established" church in the United States. And over time, the older states that did have them "dis-established" them. And the new states that sprang up in the western settlements didn't even bother about it.

One lazy summer, when I was an undergrad eons ago, some buddies and I played cribbage every evening. We decided Norm was the god of cribbage. Norm was a benign god; we were only required to sacrifice the occasional six pack of Miller High Life. Now that was a religion.