On Weather Forecasts and "Trusting the Science."

Notes from a blizzard that didn't happen. Plus a few thoughts on the current political situation.

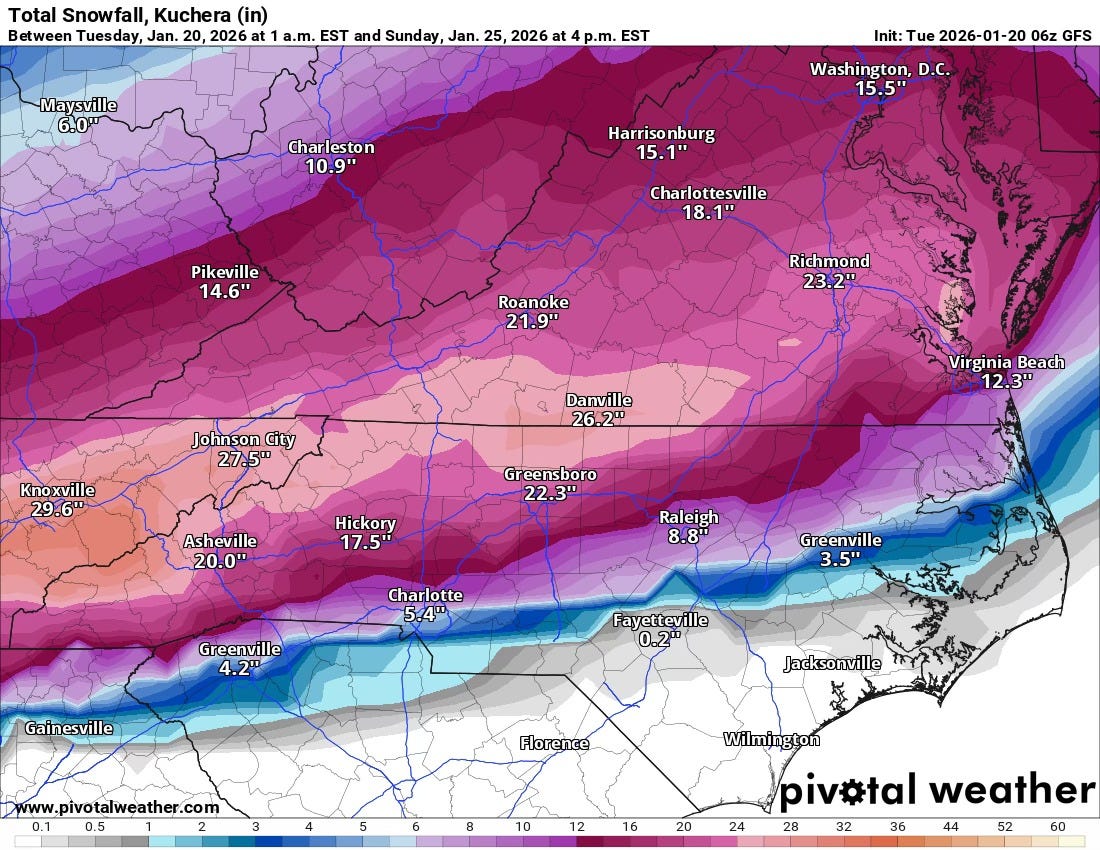

I’m writing this from Knoxville, Tennessee, where the entire town was more or less shut down by fears of a historically huge blizzard that never happened. At one point last week, there were models showing upward of 29” of snow for us:

I discounted that at the time, but the models’ consensus was still over a foot of snow.

We actually got a few flurries and some rain and sleet that never even turned into an ice storm as predicted.

Now I don’t mean to fault the weathermen, and women, too much. Theirs is an uncertain and chaotic — in the literal, mathematical sense — discipline. And big snows where I live occur when we get a clash of cold air from up north, and warm moist air from the Gulf. Mix ‘em just right and you can get a foot, or even two, of snow. Get it just a bit wrong and you get rain, or no precipitation to speak of at all.

We got rain, which is cold and depressing, but doesn’t make the roads impassable and doesn’t knock down power lines. I’ll take it.

Of course, it leaves a lot of people unhappy. Students who thought they could look forward to a day — or three — off from classes are now glumly turning to their homework. Even in my case, though I’m basically relieved not to be stuck at home, it seems like a bit of a letdown after all the buildup.

And, to be fair, the weather people hype everything now, including naming “winter storms” and summer weather events that used to just be called “blizzards” and “thunderstorms.” I understand that The Weather Channel needs viewers, and so do local news and weather broadcasts, but have too many underperforming hyped storms and people will tune out future warnings, which might actually be correct.

(We’ve seen the same thing with hurricanes, where “hurricane hype” has sometimes left people reluctant to evacuate in time after previous false alarms.)

To be fair, my local weather people did note the uncertainty in all of these predictions, to a greater degree than a few years ago, or at least so my memory suggests. And maybe there was less panic. Even yesterday evening the store shelves I saw were tolerably stocked, and not even out of bread, milk, or eggs — though you might not have found your favorite brand.

And visiting Lowe’s this morning, I found plenty of generators and bottled water on hand.

It’s possible, of course, that the early warning led stores to boost their stocks of things that would have otherwise been likely to sell out. There are reports of such stock boosts online.

It’s also possible that people panic less, having seen this sort of over-prediction before.

So what lessons are there from this experience? First, “trust the science” only goes as far as the science itself. Meteorologists can make predictions, and they’re right more often than they used to be, but they’re still wrong a lot. They simply don’t have the tools to do a better job yet, and there are reasons (like the inherent unpredictability of chaotic systems, which weather pretty much is) to doubt that they will ever be close to perfect. Most of the time people rely as much on what’s sometimes called “the persistence theory of meteorology,” assuming that the weather at present probably represents the state of the weather in the near future, and perhaps that the typical weather for a given time of year is likely to be the weather we experience again. That usually works. Usually. (You might assume that temperatures up north will be much colder than in Knoxville. You’d usually be right. But not always.)

Second, because things are unpredictable, you should be prepared for worst cases all the time. It’s a bad moment to be trying to buy a generator when there’s a blizzard prediction in the works: Supplies will be short, lines will be long, and prices will be high, and good luck if you need installation in time. It makes much more sense to buy one when there’s nothing on the horizon. Then you’ll be able to get one, and have it installed if you get one that takes installation, well before you actually need it. (We have a whole-house generator, a Generac 24 kw system that runs off of natural gas, and have for some time. When I first got it, Helen thought it was just another of my hare-brained schemes. A few weeks later during an all-night blackout, she remarked how smug she felt looking off our front porch at blacked out neighborhoods as far as the eye could see, while we had lights, A/C, and even working Internet.) Of course, being prepared means maintenance, too.

And none of this is limited to weather.

Politics is another area where lots of people make confident predictions, and are usually wrong. Usually those are predictions of doom. For extended periods, what might be called “the persistence theory of politics” works pretty well. But, as with weather, politics is a chaotic system — so, too, I have argued, is the judiciary, if you consider that outside politics, which I do not — and after long periods of quasi-stability it is prone to cough up dramatic changes that were not easily foreseeable.

As Lenin supposedly said, some decades nothing happens, and some weeks decades happen.

Are we in one of those periods now? It is, almost by definition, impossible to tell. But my advice is the same as for the weather: Be prepared for the worst, even as you recognize that most predictions of doom are probably wrong.

Ok, predicting weather is chaotic, but we totally know, within hundredths of a degree, what “average global temperature” was a thousand years ago and what it will be in a century. It’s The Science! ™

Forecasters have an incentive to err on the side of predicting doom. People don’t complain nearly as much about a predicted storm that fizzles as they would about a bad storm that blindsides them.

But—I was able to get a good price on a new generator after this last hurricane season. After another dire forecast, we got zero hurricanes hitting the mainland, and the stores were dumping their stock by late fall.