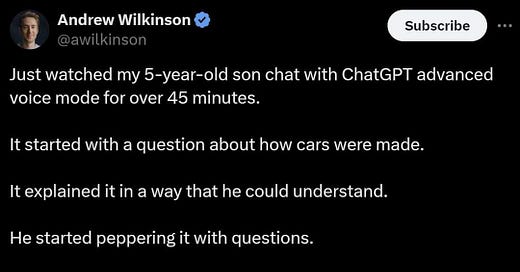

I saw this the other day, shared by a friend on Facebook. I think it’s cool.

But it also made me think about something I wrote here last year: Meet Your New, Lovable AI Buddy. I expected this prediction to come true soon, but it’s happening very fast.

I wrote:

What if the real threat isn’t that AI is super smart and kind of demonic? What if it’s just kind of smart but super cute?

Maybe instead of worrying about existential AI risk, we should be worrying about something very different.

I’m imagining a world where everyone has a personal AI assistant. Perhaps you’ve had it for years; perhaps eventually people will have them from childhood. It knows all about you, and it just wants to make you happy and help you enjoy your life. It takes care of chores and schedules and keeping track of things, it orders ahead for you at restaurants, it smooths your way through traffic or airports, maybe it even communicates with other AI assistants to hook you up with suitable romantic partners. (Who knows what you like better?) Perhaps it’s on your phone, or in a wristband, talking to you via airpods or something like that.

This is what I was thinking about when I wrote: “I kind of think the global ruling class wants all of us to have friendly, helpful, even lovable AI buddies who’ll help us, and tell us things, but who will also operate within carefully controlled, non-transparent boundaries.” . . .

Would people become attached? Probably. When my daughter was in elementary/middle school she was very into Neopets, a site that let you create your own synthetic online virtual pets. If you didn’t tend to them, they got sick and sad. Before that, millions of kids doted on Tamagotchis, the little gadgets displaying creatures that had to be fed and played with or they wilted and eventually died. By modern standards these were highly primitive, but not too primitive to inspire affection and even devotion. (And of course, humans have long gotten attached even to inanimate objects, like boats or cars.) And recent research at Duke found that kids anthromorphize robots like Alexa and Roomba: “A new study from Duke developmental psychologists asked kids just that, as well as how smart and sensitive they thought the smart speaker Alexa was compared to its floor-dwelling cousin Roomba, an autonomous vacuum. Four- to eleven-year-olds judged Alexa to have more human-like thoughts and emotions than Roomba. But despite the perceived difference in intelligence, kids felt neither the Roomba nor the Alexa deserve to be yelled at or harmed. . . .

But. Underneath the cuteness there would be guardrails, and nudges, built in. Ask it sensitive questions and you’ll get carefully filtered answers with just enough of the truth to be plausible, but still misleading. Express the wrong political views and it might act sad, or disappointed. Try to attend a disapproved political event and it might cry, sulk, or even – Tamagotchi-like – “die.” Maybe it would really die, with no reset, after plaintively telling you you were killing it. Maybe eventually you wouldn’t be able to get another if that happened.

It wouldn’t just be trained to emotionally connect with humans, it would be trained to emotionally manipulate humans. And it would have a big database of experience to work from in short order.

Well, ChatGPT isn’t quite what I describe above, but reading the post, it’s looking pretty close.

ChatGPT isn’t specifically designed to manipulate kids (its terms of use say it’s only for 13 years and older), but it is designed to manipulate people. It returns politically biased answers to queries from adults, and while it will presumably be reasonably straightforward in teaching counting, the likelihood that it won’t be turned into an indoctrination system for children once such applications become common seems low. Certainly every other educational system in our society seems to have been turned into indoctrination, and our tech lords’ enthusiasm for playing things straight down the middle appears insufficient.

The thing is, though, this sort of human/machine interaction is very appealing, and often even addictive. If these platforms exist, kids are going to use them. So what to do?

People on the right – that is, people within the mainstream of U.S. popular opinion – should find their own AI platforms. Grok is one that exists now. It might also be useful to come up with a testing and certification protocol that would let parents know which platforms are least likely to indoctrinate their kids with undesirable propaganda. There are already research protocols for that that could be expanded.

Limiting kids’ exposure to screen time (or in the case of voice access, talk time) might help too, but in fact, as the illustration at the beginning indicates, this can be a powerful teaching tool for kids. Parents may not want to sacrifice that, and policing kids’ access to screens is increasingly difficult as computers are everywhere.

But mostly I just noted that the world is moving closer to the soft-dystopian scenario I predicted back in 2023, and thought it worth pointing out. Your thoughts on how to respond in the comments will be welcome.

And as always, if you enjoy these essays please sign up for a paid subscription!

I think I need to read *The Young Lady's Illustrated Primer* one more time, to see how its aged...

AI, like many technologies, will have great advantages and great disadvantages. A disadvantage from where I sit as a History professor is that in the past year, student posts and essays have gotten considerably better in their grammar. I’m certain they are using AI, but no matter what any of the “experts” at my institution say, it is difficult, if not impossible to prove. It’s almost refreshing to read something from a student with clunky language, but I’m guessing AI could do that too, if the student gave it the right prompt. I just cannot trust that what I’m reading is actual student work, which in small ways can limit the credibility of high-performing students. I honestly don’t know what to do other than grade what I read as if it is legitimate. A possible solution would be to track every keystroke and record video of their work for the class, but that would be expensive and time consuming to monitor.

AI can provide information, however, it still has to be valid in reality. If there were a way to pair or test the information that we learn from AI with some reference to the real world that we know is accurate (verified articles/books/videos/etc. or actual people with expertise), then that would mitigate some of the possible disadvantages. The more sources of information you can access, the better. The proliferation of AI might have the ironic effect of increasing the value we place on in-person experiences. Computers are great, but people are better.