Why is the “party of youth” run by old people?

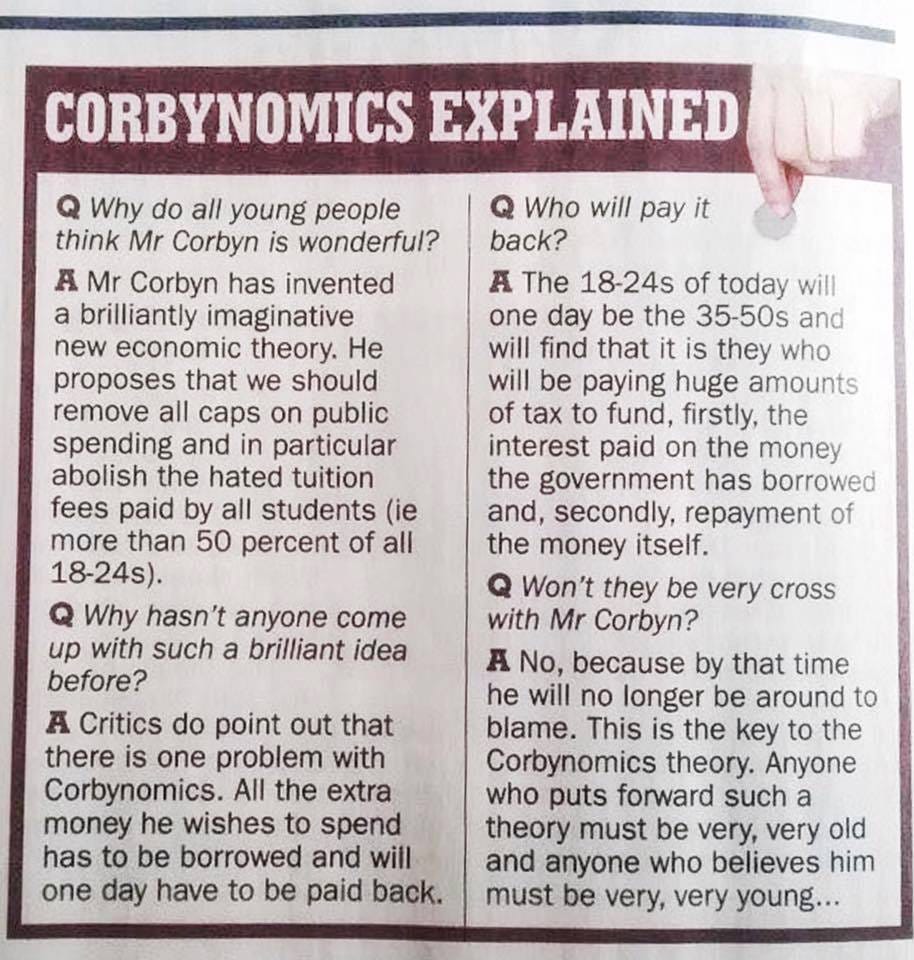

There’s an amusing piece on British Labourite Jeremy Corbyn’s economic policies that makes an important point about age groupings in modern society and politics. I’m not sure where it’s from originally, as it’s one of those things that just float around, though it’s obviously from a British magazine. I couldn’t find it via Google.

But that’s not important. It speaks for itself. Here it is:

Reading this explains a lot about why the left, in particular, relies on the politics of age, even to the point of occasionally trying to lower the voting age to 16.

And beyond voting, it helps explain why the left is always promoting youth culture, notwithstanding that its leaders, from Nancy Pelosi and Joe Biden to the likes of Noam Chomsky, are mostly so old. Leftist politics, as noted above, is something that the manipulative old sell to the gullible young. Hence leftists’ nonstop efforts to produce more gullible young people.

Young people are susceptible to socialism for a number of reasons. One is that families, by and large, actually do operate along more or less socialist lines. “From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs,” is a fair description of how most families work. Parents have jobs, earn, pay bills, care for their young, provide clothes, education, medical care and more, without the children being expected to pay their way or, nowadays, even contribute. (That last was quite different a few generations ago, when teenagers provided, on average, about a third of the household income.)

Since this works at home – certainly for the children who are the recipients of their parents’ largesse – it seems natural to expand it to society as a whole. People who have been looked after for their entire lives are likely to be comfortable with the idea of being looked after in the future.

Of course, it works at home because the parents feel an attachment to their children, and a loyalty to them, that people don’t feel for strangers. In ethnically homogenous countries, one sees a greater support for generous social benefits, because the populace is in some sense related; support for such benefits tends to drop when immigration renders those countries more heterogenous. Without such filial bonds, socialism works much less well. Except for the people at the top, of course, who look for young people to support their agendas because middle-aged people mostly know better.

But to retain the support of the younger people, they must be insulated from the objections of the middle-aged. This is done by cultivating youth culture. “Don’t trust anyone over thirty” is a famous example. The reason you’re not supposed to trust them is that they are likely to tell you that the exciting new socialist ideas you’re being fed have in fact been tried over and over again for more than a century, generally with disastrous results.

The divide was further strengthened by the invention of “cool.” As Roger Simon has written, at one time being cool was the obsession of a generation – really of several. And being cool meant, among other things, being estranged from what the squares were doing, and the squares were, by definition, the older, stable, more experienced people.

One of the reasons the “coolness” strategy worked was that young people care a lot about their reputations, and age separation in our education system (more on that in a bit) means that the people whose reputations they care about are mostly other young people.

It didn’t used to be that way. That modern invention, the “teenager” as a separate category, didn’t really exist historically. In the Middle Ages and before, teenaged people were diplomats, soldiers, etc. (George Washington bossed a wilderness survey team in his teens.) Teenagers as a separate category, a group segregated by age in the educational system and treated as a distinct marketing niche, are a phenomenon of the last century or so. As Thomas Hine writes, they were a creation of universal public high school, which took them out of the workplace and concentrated them with others their own age. Coolness depended on that. As Simon writes, “cool depended on a hive mind in the first place. It was little more than fad.”

But what a powerful fad. Not only did it drive Frank Sinatra, Elvis, and the Beatles, but it drove the Hippie Movement, the New Left, the Kennedy Administration, and more. (As late as 2004, John Kerry – billing himself as John F. Kerry for the presidential election – was trying to suck the last dregs of Camelot coolness out of the pot, though if there’s anything Kerry has never been, it’s cool.)

Before teenagers became a distinct group – as Hine notes, the term was first used in 1941 – they spent a lot of time in the workplace, among adults. They still valued reputation, but the reputation in question came from those adults as much as (or more than) from others of their own age. Being in your teens was about trying to prove yourself to adults, not so much about trying to impress your peers.

In an earlier piece, I quoted from a book by Paul Allen and Claudia Worrell, in which a man describes his experience working with adults, but I’ll repeat that passage here:

Anderson and Worrell contrast school with the experience of a man named Pete who worked as a teenager in a men’s clothing store in New Hampshire in the 1970s, where he was the youngest employee by twenty years. The work wasn’t exciting, but people depended on him to get it right:

“Even at age fifteen I knew that folding shirts was kind of trivial,” he recalls. “Whether or not I flicked the cuffs in onto themselves just right to make them lie flat, I knew was not a life-changing event. What was a life-changing event was that I realized that these ‘men’s men’ weren’t going to consider me one of their club until I knew how to do it correctly, and I demonstrated that I could be relied upon to do it correctly again and again, because to them, even though they knew they were working in a relatively inconsequential job, this was the way that they displayed their pride, their craftsmanship. They let me know that it was important that I shared this focus, or I would never be trusted to be in the club. … This job also made me see that it was important that, every day, I show up, and on time because these guys were waiting to take their own break until I covered one of them in the store. So my being there was not some silly after-school job. It was, I began to see, a small cog in what made that place successful. … For me, that first job was a permanent character builder. It taught me: Show up on time. Do what you say you are going to do. Finish what you begin.”

Anderson and Worrell note, “These adult men had become Pete’s peer group.” After working there for a while, he reports, “I lost a bit of interest in gaining acceptance from my peers and realized that it was much more fun and more interesting to gain acceptance from people who you can learn a lot more from.” Pete was lucky because he got to experience something that too many kids don’t get to experience today—real work, outside school, with real adults.

And that’s by design. The crusade against “child labor” – which now, ridiculously, includes such things as 17-year-olds with paper routes if you’re unfortunate enough to live in California – was partly about promoting union jobs, but also about increasing the separation of young people from the real world. The promotion of college education for all is more of the same, turning college into an extended version of high school. (Though arguably many aspects of college today are less demanding of academic skill or discipline than was the high school of the 1930s.). The important thing is to keep “peer culture” going on as long as possible.

Modern society has extended adolescence well into the 20s for many people and, I want to stress, that’s not by accident. Separation of young people from the larger society helps create a captive cadre of voters, protesters, campaign workers, etc. There are, of course, other forces promoting this separation besides left-politics (companies like to market to young people for the same reasons of hive-mindedness and gullibility) but it’s worth keeping in mind what’s going on here, and why.

And the solutions involve getting young people back out into the real world, instead of concentrating them in age-segregated ghettos. We should make it easier for teens to hold part-time, or even full-time jobs. With online and home-schooling there’s no reason to assume they have to be warehoused during the middle of the day: My daughter did online school at night, and held a day job at a TV production company from 14 to 16, when she went off to college. We had insisted that she get a job at 14, and she’s very glad we did now.

A return to the Reagan-era subminimum wage for teens would also help. A classmate of mine at law school got hired on at a swimming pool at 15 because of that wage and thinks the work experience changed his life. (It’s those swimming pools again!)

And higher education needs to be shrunken, and replaced in many cases by trade schools and apprenticeships. It’s questionable today whether many degree programs actually add value, but they do keep human capital tied up, even as the students run up debts. And many have their lives ruined by alcohol, drugs, or sexual misfortunes.

At least, colleges should require that people hold a job for a couple of years before attending, to provide a taste of the real world.

These reforms would all be bitterly opposed by the status quo, of course. But the reasons for that opposition have nothing to do with the well-being of young people, or of society.

Huzza! The Instapundit has nailed it. All that he missed is that the deliberate gathering of the Gullible Young into politically-herdible cohorts was precisely what the early Soviets did by creating the Komsomol and Young Pioneers for the use by the Party as 'influencers' to preserve the purity of the mandatory groupthink.

"Pete was lucky because he got to experience something that too many kids don’t get to experience today—real work, outside school, with real adults."

For some years I tutored HS-age kids on film/TV/stage sets. Far from the 'showbiz brat' image, the kids were almost uniformly smart, well-mannered, and very good at navigating a world where time was a lot of money and that had little room for actors acting-up. So they showed up on schedule, knew their lines, hit their marks, and sat down to meals with a mostly-adult group of co-workers.

Of course, it also helped that they were paid decently and fully cognizant of how lucky they were to be working in a highly selective industry with some fun perks.