Is the “great filter” simply choice?

People looking for alien civilizations have posited that we haven’t found any because something kills them off before they reach the point of being able to travel across interstellar distances. This “something” is an unknown – monsters from subspace? Nuclear, biological, or nanotechnological war? -- but whatever it is, it's generically referred to as “the great filter.”

Humans would – mostly – prefer that we not be filtered into nonexistence. But of course other intelligent species would presumptively prefer that too. So if a filter exists, it must be something about which they have no choice.

But maybe the filter is choice: Choice whether or not to reproduce. And maybe we don’t have a choice about that anymore.

One of the things about pretty much all human societies until recently is that they put pressure on their members to have children. Some of that pressure was provided by nature in the form of hormones and sex drive, but some of it also came from societal/cultural pressures to reproduce. Get rid of those and people have fewer kids.

One example is China, where rates of marriage and childbirth are plummeting, far below replacement. As the New York Times recently reported, even backing away from the one-child policy hasn’t changed things. Chinese of 50 years ago wanted lots of kids. Chinese today, on the other hand, don’t care so much. The cultural chain has been broken, and it won’t restart itself just because the Party realizes it made a big mistake. People got used to smaller families, and to lifestyles that make bigger families harder and more expensive.

Add to that the social and financial uncertainties created by dictatorial government, and, well, no children please, we’re Chinese:

Grace Zhang, a tech worker who had long been ambivalent about marriage, spent two months barricaded in the government lockdown of Shanghai last year. Robbed of the ability to move freely, she spiraled over the loss of control. As she saw the lockdowns spread to other cities, her sense of optimism faded.

When China reopened in December, Ms. Zhang, 31, left Shanghai to work remotely, traveling from city to city in hopes that a change of scene would restore her positive outlook.

Now, as she sees rising layoffs around her in a troubled economy, she wonders if her job is secure enough to sustain a future family. She has a boyfriend but no immediate plans to marry, despite frequent admonishments from her father that it’s time to settle down.

“This kind of instability in life will make people more and more afraid of making new life changes,” she said.

The number of marriages in China declined for nine consecutive years, falling by half in less than a decade. Last year, about 6.8 million couples registered for marriage, the lowest since records began in 1986, down from 13.5 million in 2013, according to government data released last month. . . .

“At the moment, I’m still looking for stability and seeing what’s going on with the economy,” said Mr. Xu, who lives in the southwestern city of Chengdu.

Until 2020, Erin Wang, 35, was optimistic about living in China. Then, she saw the government crack down on private companies, killing jobs in the process, and take a heavy-handed approach to the pandemic. She grew concerned about the increasingly authoritarian environment.

“I felt like I had no confidence to have a baby in China,” she said.

So sorry, Chairman Xi. We don’t make babies here now. At least not nearly as many. We don’t even get married nearly as much.

Tough luck for the Chinese, we might say smugly, but it serves them right. Er, except that something more or less like that is happening pretty much everywhere. Birth rates are way down everywhere – even in sub-Saharan Africa, though the trend there started later and has further to go – and we can’t blame that on the one-child policy.

In Japan and South Korea, which never had the one-child policy, birth rates are frighteningly small. South Korea has the world’s lowest birth rate: “The country’s fertility rate, which indicates the average number of children a woman will have in her lifetime, sunk to 0.81 in 2021 – 0.03% lower than the previous year, according to government-run Statistics Korea. To put that into perspective, the 2021 fertility rate was 1.6 in the United States and 1.3 in Japan, which also saw its lowest rate on record last year. . . . To maintain a stable population, countries need a fertility rate of 2.1 – anything above that indicates population growth. South Korea’s birth rate has been dropping since 2015, and in 2020 the country recorded more deaths than births for the first time – meaning the number of inhabitants shrank, in what’s called a ‘population death cross.’”

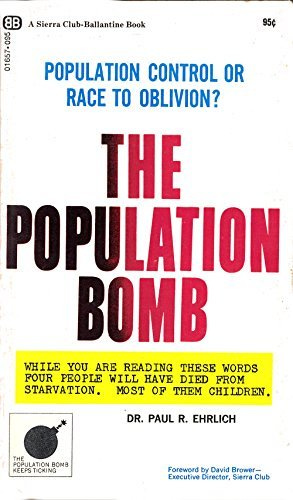

It's all part of what Brink Lindsey calls a “global fertility collapse.” He calls it that because that’s what it is. “The defusing of the population bomb was a triumph of capitalist wealth creation — but it came with a catch. Birth rates fell enough to avert Malthusian catastrophe, but then they kept right on falling. In the 1970s, sub-replacement fertility rates — that is, rates below the roughly 2.1 children per woman needed to maintain a stable population — began cropping up in rich democracies. But low fertility didn’t confine itself to rich countries; it kept spreading. As of now, roughly half the world’s population resides in countries with sub-replacement fertility.”

People are having fewer children, for the most part, because they simply want fewer children. Oh, there are contributing factors: Fascinating research in the United States suggests that car seats have a contraceptive effect, and not just because they take up the back seat. Well, actually it is because they take up the back seat: “Since 1977, U.S. states have passed laws steadily raising the age for which a child must ride in a car safety seat. These laws significantly raise the cost of having a third child, as many regular-sized cars cannot fit three child seats in the back. Using census data and state-year variation in laws, we estimate that when women have two children of ages requiring mandated car seats, they have a lower annual probability of giving birth by 0.73 percentage points. Consistent with a causal channel, this effect is limited to third child births, is concentrated in households with access to a car, and is larger when a male is present (when both front seats are likely to be occupied). We estimate that these laws prevented only 57 car crash fatalities of children nationwide in 2017. Simultaneously, they led to a permanent reduction of approximately 8,000 births in the same year, and 145,000 fewer births since 1980, with 90% of this decline being since 2000.”

But fascinating or not, the real reason people are having fewer children is because they want fewer children. Governments try to offset this with subsidies – and we’ll see (much) more of that in the future – but the fact is, the financial, emotional, and energy costs of having children are so high that no plausible government subsidy is going to offset them. Subsidies may have a small effect at the margins, and maybe another small effect in terms of setting social preferences, but it’s unlikely that they’ll offset the pleasures of sleeping in, or of taking expensive vacations, or advancing one’s (or two’s) careers enough to change most people’s minds. If it costs a million bucks to raise a kid, it’s going to cost at least that much in subsidies to really change people’s minds.

Of course, there’s always the stick as well as the carrot. In the old days, which ended around the time I was born, the social pressures to have children were enormous. Birth control existed, and people were already having fewer children than their parents, but the lack of many alternatives for women tended to steer them into marriage and children. You could be a nurse, or a teacher, or a librarian, or a nun, but what you were mostly expected to be was a mother. Some women bucked the trend, but most didn’t. Men, meanwhile, were more likely to get promotions if they were married with children. And, as my mother recounts, even when you were legally an adult, in her day you weren’t considered fully a grownup until you were married and had kids.

Nowadays, it’s kind of the opposite. Minivans are looked down upon, and SUVs – which for most people function essentially as minivans with plausible deniability – are popular, because SUVs don’t have the strong connotations of parenthood. Minivans are “mommymobiles” and that’s not cool.

Some of this comes from marketing pressures – its easier to sell things to singles, or to DINKs (Double Income, No Kids) than to parents. But some of it comes from people’s own desire for independence and less responsibility. And again, that’s not just in our culture, or China’s, but is happening everywhere.

On an individual level, of course, it’s great that people are free to have fewer children, or no children, if they want. As Elton John informs us, if you choose to, you can live your life alone. But at a societal level, declining birth rates pose a lot of problems. First of all, they’re fatal to the Ponzi schemes that comprise most retirement and pension plans. And even without Ponzi schemes, retirees can only claim a share of whatever wealth is available in general when they retire. Individuals can save for retirement, but societies really can’t, since even stored-up wealth is just a claim on the productive capacity available when people (or maybe I should say generational cohorts) hit retirement. If the population is smaller, there will be less wealth available, probably, and at any rate the retirement costs will be spread over a smaller group, meaning that the remaining individuals will feel the pinch more.

Societies laboring under “population death cross” are also likely to be less dynamic. Older people aren’t as hidebound as popular culture would have it – most successful entrepreneurs are well into middle age, and some are downright old – but there’s still a measure of truth to that idea. And fewer people just means fewer sources of ideas, innovation, and energy.

Anyway, it’s at least conceivable that wealthy, technologically advanced societies in general hit a death spiral: Fewer people, less dynamism, fewer children, etc.

Alternatively, more traditional cultures will gradually replace everyone else simply by continuing to breed. (In American history, the Shakers died out, the Mormons flourished). Perhaps in a few generations the world will be disproportionately composed of Amish, Mennonites, Orthodox Jews, fundamentalist Muslims, traditionalist Catholics, and the like.

Such a world might get along fine, at least from the perspective of its inhabitants, but be less disposed to interstellar travel, which suggests that the great filter may not actually be fatal to a species, just to its capacity to be noticed by others.

I don’t know, but I suspect that after over half a century of policies built, explicitly or implicitly, on Paul Ehrlich’s bogus Population Bomb claims, we’ll see governments trying, with increasing degrees of desperation, to encourage people to marry and have kids. (It’s possible that the U.S. Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on contraception and abortion was influenced by “population explosion” worries, and it’s possible that the Dobbsopinion, reversing Roe, represents a retreat from these concerns. And in Texas alone, the post-Roe era reportedly led to 10,000 more live births in the first year than would have happened under Roe.)

The thing is, it’s a lot easier to encourage people to do things that are easy and fun – like have sex without having kids – than to do things that are difficult and sometimes unpleasant, as raising kids certainly can be. So my suspicion is that the global population bust is going to go on for quite a while.

Am I wrong?

As always, please share your thoughts in the comments, and if you like this piece please consider becoming a paying subscriber.

"Perhaps in a few generations the world will be disproportionately composed of Amish, Mennonites, Orthodox Jews, fundamentalist Muslims, traditionalist Catholics, and the like." this is the most optimistic thing i have ever read.

Just an ironic comment. I was one of the organisers of the first earth day at my university. During the run up to the “day” and the day itself I found most of the other participants, both students and faculty, to be insufferable hypocrites. I therefore did, not quite the opposite, but married and had four children. I thought my actions made up for my youthful indiscretion.